This work is based on “The History of the New England Folk Festival 1944-1994” published by NEFFA during for its 50th Anniversary Festival. This was edited by Tony Parkes, and was based on the following sources: articles by Ralph Page and Louise Winston in Northern Junket, previous Festival programs, and a special booklet printed for the 10th Festival. Further updates since 1994 have been made by Dan Pearl.

1944

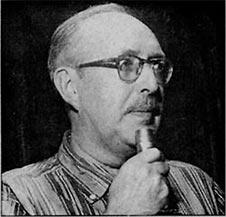

IT was the summer of 1944. Three people were chatting over coffee after a Tuesday night square dance at the Boston YWCA: Grace Palmer, director of the Y; Mary Gillette, head of its physical education program; and Ralph Page, the popular New Hampshire caller who presided at the square dances. The series had been running for little more than a year, but was already drawing over two hundred people every week, most of them college students.

As Ralph Page later recalled the conversation, they were discussing a recent attempt at a “New England Folk Festival” at Boston Garden which had left them unimpressed. “Suddenly, Mary said, ‘Why don’t we have a real folk festival?’ and so the idea was born — as simple as that!”

The idea had probably been germinating for a while. That spring, the governor of Massachusetts had held a Conference on Recreation, with leaders from all over the state discussing ways to counteract wartime stress in people’s lives and promote understanding between cultures. Successful programs were already underway at the Boston YWCA and at the International Institute. Mary Gillette envisioned a festival where New England’s many ethnic groups could share their song, dances, and crafts and present them to a wider audience — not in a commercial, isn’t-this-quaint way, but in a simple, honest, straightforward manner.

It was an idea whose time had come: everyone was enthusiastic. Grace Palmer offered the facilities of the Boston YWCA. Philip Sharples, who in 1940 had founded the Belmont Country Dance Group (one of the first square and contra dance series in the Boston area), joined with Mary Gillette and Ralph Page in calling local leaders to meet and talk it over. Many recreation agencies and ethnic groups sent representatives, who wasted no time in getting down to business. From the start, the Festival Committee agreed to maintain an atmosphere of non-commercialism and high standards of performance and authenticity.

The first event, modestly billed as a “Fall Folk Festival,” was held at the Boston YWCA on October 28 and 29, 1944. According to Louise Winston, about 200 people attended. There were afternoon and evening sessions on both Saturday and Sunday. Each session began with craft exhibits and demonstrations in the auditorium, followed by music and dance performances in the gym, three floors up. The evening sessions ended with folk and square dancing for all, with Ralph Page calling. Fifteen musical groups and 24 dance groups performed; the program listed 13 craft exhibits. Two leaders’ conferences were held on Sunday: one on arts and crafts, the other on music and dance.

Of the performers at the first Festival, the Irish, Lithuanian, Polish, and Swedish dance groups have been coming ever since, as has the Country Dance Society, Boston Centre with its English dancing. Six different groups presented American dances; for many years thereafter, a prominent feature of the Festival was the performing of “ordinary” squares and contras by numerous sets of schoolchildren and adults. Another longtime tradition was a set of dance tunes “just for listening” at each session, played by some of New England’s finest old-time fiddlers. The 1944 Festival was more culturally inclusive than some later ones: the program included music of the Wampanoag and Navajo tribes, as well as Negro spirituals and songs from China (nothing from Germany or Japan, though!).

A note at the end of the printed program read: “If you feel this is a valuable endeavor and would like to see it continue, please write the Committee.” Whether it was a spate of letters or simply the enthusiasm of the organizers that prompted the action, the Festival became an annual event. The next three Festivals followed the pattern of the first: same site, same time of year. A tradition begun in 1945 and continued for many years was group singing by the audience midway through each session. In 1947 an exhibit of folk costumes, music, and books was so well received that it became an integral part of the Festival. Also in 1947, the craft area had a central theme: work in textiles.

1948

In 1948, the Committee decided to delay the 5th Festival to the spring of 1949, to coincide with the national convention of the American Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation. Perhaps because of the proximity of the convention, the dance workshops and leaders’ conferences were unusually well attended. For the first time, performing dance groups outnumbered singers and choirs by more than three to one: many of the older ballad singers who had graced the early Festivals had passed on, and group singing was steadily becoming more popular. Again the craft area had a theme: woodworking, old and new.

A spring Festival proved more desirable than one in the fall, as most participating groups followed the academic calendar and a spring date gave them more time to prepare. The sixth Festival was held in May of 1950, again at the Boston YWCA, with fewer performances and more time given to general dancing. There was no craft area.

By this time the Festival had outgrown both its space at the YWCA and the loose coalition of volunteers. A set of bylaws was drawn up shortly after the 1950 Festival and adopted in October; on November 28 the New England Folk Festival Association, Inc., received its charter. NEFFA’s first concern was to find a larger space; this was done in time for the seventh Festival, held at MIT in March 1951. There were three sessions — Friday evening, Saturday afternoon, and Saturday evening — setting the pattern for many years to come. The extra space was a boon: attendance jumped from 1,700 to 3,000. Audience participation was emphasized, with short sets of general dancing or singing after every two or three performances. For the first time, dance leaders from outside New England were invited. Each session began with a procession of all the participating groups.

It was time, the planners felt, to try holding the Festival outside the Boston area. Worcester was a logical choice: it was centrally located, and many enthusiastic dancers and leaders lived there. In 1952 and 1953 the Festival was held at the Memorial Auditorium in that city, with a long list of sponsoring organizations and individual patrons. Some innovations of those years have continued to the present: in 1952 craftspeople were first allowed to sell their wares, and 1953 saw the first ethnic food. The latter was a far cry from today’s cornucopia — only the Italians, Poles, and Scots had booths!

1954

In April, 1954, the tenth New England Folk Festival was held in Medford, Mass. at what was then Tufts College. There was a sign of things to come: for the

first time, a second gym was opened for continuous dancing. The usual program went on in the main hall, with the short sets of “dancing for all” that had become standard, weighting the Festival heavily toward audience participation. The food area grew from three booths to fifteen; the printed program included advertisements for callers and folk-related businesses.

The 1955 Festival was also at Tufts. Again the program was expanded, this time to include a Sunday afternoon workshop, “free to members and only for members.” From 1955 through 1973 this workshop gave NEFFA members a chance to learn more intricate folk and square dances from well-known leaders under less crowded conditions. No doubt it encouraged many people to pay their dollar and become members!

The Festival returned to Worcester in 1956. The printed program listed the complete schedule for the lower hall, with a different caller every ten minutes. For the first time we can get an idea of what was being danced: squares vastly outnumbered contras. The most notable feature of 1956 for old Festival hands may have been the absence of Ralph Page, who was teaching contra dances in Japan on a State Department-sponsored tour.

1957

In 1957, the Festival left Massachusetts for the first time, moving to Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire. Like Worcester, Exeter was a hotbed of interest in folk music and dance, with many local enthusiasts ready to join or head up committees. Again there was continuous dancing in a second hall; even in New Hampshire, squares were the order of the day. A musicians’ jam session and a folk singing session were held in a separate room between the Saturday afternoon and evening programs. In addition to crafts, the program book listed “specialty exhibits,” that is, folk-related items not made by their vendors. (This category was later called simply “exhibits,” and is now the Folk Bazaar.) A directory of callers and businesses, who paid to be listed, replaced the display ads.

After two more years at Tufts, one at Exeter, and another at Tufts, the Festival moved south of Boston for the first time. The 18th Festival was held in April, 1962 at Bridgewater State College. Square dancing had flourished on the South Shore since the late 1940s, and many local people pitched in to make the Festival a success.

The Festival continued to move around New England: Lowell (Mass.) Memorial Auditorium in 1963, Manchester (NH) Armory in 1964, and Saugus (Mass.) High School in 1965. Details varied — there was no second hall at some locations, and no Friday night program in Lowell — but in general, the tried and true formula worked well.

1966

In 1966, at the urging of Rhode Island members, the Festival moved to North Kingstown High School in the Ocean State. It may have been an artistic success, but financially it was a disaster: attendance fell far below projections.

Nothing daunted, the Committees got up, dusted themselves off, and headed for Natick, Massachusetts in 1967. Natick High School turned out to be one of the best locations ever, and the Festival stayed there for four years, more than recouping its losses.

In 1967, Josephine Bemis, who with her husband Chuck was instrumental in obtaining the Natick site, instituted a Saturday morning program for children who were learning international folk dances at school. The student groups showed each other what they had learned during the year, then combined for some general dancing. This program, later called the Jamboree, continued through 1981.

The Festival program continued largely unchanged through the next few years — King Philip High School in Wrentham, in 1971; Wellesley High School in 1972; Brockton High School in 1973. Perhaps the most notable trend is more visible in retrospect: the number of American dance demonstrations had been dwindling steadily, and in 1973 there were none. This reflected the diminishing number of groups that were organized enough field a demonstration team, yet favored the more traditional square and contra dances. Western square dancing had reached New England in the late 1940s and was included in NEFFA Festival programs through the mid-1950s, but since that time the gulf between the styles had widened.

1974

The NEFFA Board now decided that finding a permanent location would be better for the Festival than moving from town to town. In 1974, for its thirtieth year, the Festival returned to Natick, for a multi-year stay. Staying in one place (at least for a while) gave the Festival a chance to build attendance while cementing local relationships.

Several changes were made in 1974. For the first time in Natick, a second hall was opened for dancing. It was referred to as the “Special Hall” for the first two years, then assumed its current name, the Small Hall. (Gym equipment was not stored there at that time — there really was room to dance!) Friday evening was devoted entirely to continuous “dancing for all”: international folk in the Special Hall, squares and contras in the Main Hall. The performing dance groups that would have appeared on Friday were moved to Sunday afternoon, replacing the members’ dance workshop. A small stage was set up in the cafeteria for concerts, puppet shows, and some dance demonstrations. A Music Hall (the present Exhibits Room) was opened for jam sessions and a few choral and instrumental workshops. The spacious Crafts Hall accommodated 37 booths, up from 23 the year before.

The changes in 1975 were few but momentous. The Lower Hall was opened: for the first time, Festival-goers had to choose among events running simultaneously in three dance halls and a full-time Music Room. To help folks keep track of things, a schedule grid appeared in the center of the program booklet (the grid eventually became a separate sheet that could be carried in a pocket). And for the first time, contras outnumbered squares in the sessions devoted to general dancing.

1976

The 1976 Festival continued in the now proven format. The player piano took up residence in the Cafeteria. Many dance musicians who got their start in the Festival Orchestra had by now formed bands of their own; the 1976 program listed these groups by name. No special ceremonies marked the Bicentennial of the nation; Ralph Page was irritated enough to spend most of the weekend at the New England Square and Round Dance Convention, but showed up in Natick long enough to lead a session of Revolutionary-era contras.

In 1977, the program booklet mentioned outdoor Morris dancing for the first time, although it had doubtless been done unofficially in prior years. One short-lived innovation stemmed from the growing trend towards organized dance bands. At the request of some of these groups, several hours of general dancing in the Main Hall were assigned to “name” bands, with only a few slots saved for the Festival Orchestra. For a number of reasons, including the acoustics in the Main Hall and a desire for a more inclusive feeling on stage, the experiment was scrapped after one year.

In 1978 the Festival expanded to the Auditorium Stage, used exclusively for dance workshops that year. The folk music and song program was expanded too, with a separate “Coffeehouse” in a room off the Cafeteria (to the right of the food booths). The Small Hall was renamed the Music Room, although it still hosted many dance events. The old Music Hall became an Exhibits Hall, for private collections and displays that were not offered for sale; the vendors’ booths in the corridors, formerly called “Exhibits,” became the Folk Bazaar. For the first time, the Program Committee provided a full schedule of workshops for children on Saturday and Sunday afternoons.

In 1979, the Coffeehouse moved to its present location in the school’s music room. The old Coffeehouse was used for several years as a rehearsal area for dance demonstrations. The program book shows a record number of organized musical groups: 21, up from 15 the year before. As many younger names as older ones appeared in the lists of dance leaders and Committee members.

1982

The next significant changes took place in 1982. The Auditorium Stage now hosted concerts and performances as well as dance workshops. And the Saturday Morning Jamboree for schoolchildren, after a run of 15 years, was no more. These changes had the effect of shifting the focus of the Festival away from the Main Hall, making the weekend feel even more like a multi-ring circus.

The fortieth Festival in 1984 was an occasion to look back on many years of success and to honor the three people generally recognized as founders: Mary Gillette, Ralph Page, and the late Philip Sharples. At a special ceremony on Saturday evening, plaques were presented to the surviving founders, and Ralph Page called old-time contra dances to a group of dancers who had attended the earliest Festivals.

With a string of successful years in Natick, the NEFFA treasury had money to spare. During the 1984-85 season, NEFFA awarded $2650 in grants to support field research on the music of Bulgaria and the Shetland Islands, new dance series in Rhode Island, and a NEFFA-style festival in Pennsylvania. The Grants Committee has been funding similar projects ever since.

The 1985 Festival was significant in several ways: the folk music program expanded into the Chorus Room; the first half-hour contra medley appeared in the Main Hall; and Ralph Page was no longer alive. His presence as caller, organizer, and raconteur had colored every previous Festival but one, and he had a special status as the last founder to remain active in NEFFA (Mary Gillette had left the area). His passing was mourned by all, but it was clear that enough people shared his vision to keep the Festival going for years to come.

Not all of those dedicated folks were New Englanders. The 1985 program lists callers from New York, New Jersey, Michigan, Missouri, and California. This is the first real indication of another significant change: since the mid-1980s, the NEFFA Festival has increasingly served as a gathering place for contra dancers, musicians, and callers from across North America, becoming in effect a “national contra dance convention.”

1986

In the 1986 program, the list of bands and musical groups included their members by name — two pages of fine print. Morris and sword dancing had become a major part of the Festival: the program listed two dozen teams.

During 1986, the NEFFA Board established a Ralph Page Memorial Committee to continue Ralph’s work and memorialize his name. The Committee’s first act was to purchase Ralph’s book and record library from his widow, Ada Novak Page, and donate it to the University of New Hampshire at Durham. Since 1988, the Committee has run the Ralph Page Legacy Weekend (renamed in 2000 to the New England Dance Legacy Weekend) at the University, combining dance workships and parties with seminars for callers, musicians, and folklorists.

A sharp-eyed observer will see in the 1987 Festival program two indications of the crowding in the dance halls that had become legendary: the map of the school shows the “Lower Hall Overflow” as an official area, and a note appears to the effect that “NEFFA encourages all dancers to exercise care in their dancing.”

In 1989 the program book dropped the complete list of events in the Main Hall, which had become merely a duplicate of information on the grid, and replaced it with an alphabetical index of performers. (The dance performances were still described in detail.) With the Main Hall used for specialized workshops as much as for general dancing, the shift in focus was complete. The Festival had grown so big that no single hall could hold everyone for general or “official” events, and the Main Hall lost a good deal of its “main” character.

And morris and sword dancing reached a new level of recognition with a two-page spread in the program giving a complete schedule of performances and list of 28 teams from as far away as New Jersey, including team colors so fans could identify their favorites.

1994

The Festival has continued into the ’90s, seemingly with more performers, exhibitors, and attenders every year. In 1991 yet another room was opened for Festival use: first called the Discussion Hall, it became the Lounge the following year. In 1993 its name changed again, to the Natick Room, while a new South Room (between food and exhibits) hosted several discussion sessions.

In 1994, the 50th New England Folk Festival marked a proud milestone in NEFFA history. During a special anniversary program in the Auditorium, NEFFA founder Mary Gillette, who had been flown in from Ohio for her final appearance at the Festival, was given special recognition.

The Festival has grown through the years; hundreds of volunteers serve on a dozen committees to meet the needs of thousands of Festival-goers of all ages. But throughout its long run, it has held to its original principles of non-commercialism, high standards of performance and authenticity, and an inclusiveness that has valued audience participation as highly as performances. True to its founders’ vision and the goals set forth in its first bylaws, the Festival has done its part “to preserve folk traditions in New England and elsewhere, and to encourage the development of a living folk culture.”

1995

(subsequent text written by Dan Pearl)

The South Room was not available to NEFFA. To accommodate the discussions previously held there, the Art Room, located in the Auditorium Wing near the Performer Sales table was opened up. During unscheduled times, the room was designated as a “rest area”. To help alleviate the parking problems near the school, an additional satellite lot at Natick Labs (now the U.S. Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center (NRDEC)) was opened with free shuttle bus service. (This location was closed to parking in 2002 due to security constraints imposed after the 9/11 attacks.)

A strong supporter of NEFFA and its goals from almost the beginning was Ted Sannella, who died in November 1995.

In 1996, the art exhibition in the Exhibits Room was discontinued. In its place was the Activity Room: a hands-on room for kids mostly, but also adults. A new room for folk music and workshops opened up to us. This room (confusingly called the South Room), is located at what was previously a quiet corner of the school, just down the hall from Performer Sales. Yet another room, the Loft (above the Natick Room), became available for discussions and music. The NEFFA presence on the World Wide Web went from a single page to a multi-page affair, with on-line schedules, performer information, and details about NEFFA’s other offerings.

The Festival of 1997 presented a challenge to all. The school had refinished the floor in the Main Hall in the fall and required special footwear restrictions by Festival-goers. A public education campaign was done, and shoe-cleaning stations were established outside the Main Hall. Thanks to the cooperation offered by thousands of people, after the Festival the school staff remarked that they couldn’t tell that there had been a Festival, the floor was in such good shape. The Art Room was redesignated as the full-time Rest Area, and was equipped with gym mats for impromptu naps.

Mary Gillette, the last of NEFFA’s surviving founders, died on May 20th, 1997. Her niece, Barbara Shelton, said “The Folk Festival was never far from her mind and she loved telling others of the trip we had there for the 50th Anniversary.”

As the Festival Committee became aware of the restrictions and requirement of the Americans With Disabilities Act, certain changes were made. In 1999, official programming was removed from The Loft and the South Room, as they were not accessible to those in wheelchairs. Assistive listening devices were also available on a limited basis.

Replacing the lost program areas were the North Star Room (used for discussions, mostly), and the Lyric Room.

2000

In 2000, NEFFA had its own Y2K issue: the “traditional” Festival dates had conflicts with Easter and Passover, so the Festival was run at the beginning of the school vacation, rather than the end. School was in session until 2pm on Friday, and the Festival set-up crew needed to move in and set up…fast! We did take a few short cuts to ease the setup (e.g., no Crafts Room on Friday night), and the program was 1/2 hour shorter, but for the most part, it felt like a regular Festival.

In 2001, we opened up the Loft for some supplementary showings of “Paid to Eat Ice Cream”, a video about Bob McQuillen that was produced by David Millstone. An ominious question on the evaluation form asked people about alternate venues. This was in response to the possible renovation of the High School that is being considered by the town of Natick.

Just before the 2005 Festival, the town of Natick rescinded permission to use the Lower Hall, as it is now a “Wellness Center” filled with brand new fitness equipment and rubber floor (despite NEFFA’s offer to remove and replace the equipment and floor). The Program Committee needed to shuffle the program quite a bit, and the Lower Hall that we could use was actually the Overflow Hall.

In 2006, to address the previous year’s problem, we rented a very nice 80’x40′ tent and dance floor. The mid-40F degree rainy weather made this a chilly place to dance, but dancers discovered a unique energy and comfort dancing in the open air. The $12,000 expense for the tent was not one that we can afford on an annual basis, and talk was also in the air about possible sites that could suit our needs better.

2007

A turning point for NEFFA: A new site! Persis Thorndike was hired by NEFFA to conduct a site search. Of the sites turned up on the short list, the one that had the most promise was Mansfield High and Middle Schools. Countless hours were spent by committee members on site visits and planning meetings to make the transition as smooth as possible. Of course it wasn’t without its rough spots. The Mansfield staff made us feel more welcome than we have felt in a long time, and for many, the essence of the Festival survived the move. We looked forward to the challenges and triumphs of the future!

2009

Mounting financial losses spurred the Festival committee into several actions. Prior to the Festival, a benefit dance raised around $6000! Cost-cutting measures were instituted but did not impinge on the quality of the program. These measures, plus generous donations, helped the Festival get into the black.

2013

NEFFA makes the funny papers! See this Pearls Before Swine strip!

2013 was memorable for an unanticipated reason. Earlier that week, explosions rocked the finish line of the Boston Marathon. The ensuing manhunt in Watertown kept performers and volunteers from coming to the Festival on Friday. The Festival committee was considering cancelling the event, but people stepped up, and covered the critical responsibilities in a timely manner. Early Friday evening, the word of the apprehension of the second suspect filtered through the halls, and people danced with feelings of giddy relief and renewed joy.

2020

After the Festival in 2019, we got word from the Mansfield Schools that they were planning major reconstruction during the time scheduled for the 2020 Festival, sending us into a panicked search for a new site for 2020. We discovered Acton/Boxborough Regional High School, which offered a lot of interesting spaces, but it would be an imperfect fit for us. Final preparations were feverishly being made when a little thing called the coronavirus showed signs of becoming widespread. With a combination of regret and relief, we cancelled the in-person Festival for 2020. In lieu of a full-blown Festival, we released a collection of recorded performances.

2021

NEFFA made the transition into the virtual world with a one-day online Ralph Page Dance Legacy Weekend in January. We followed up this success with a full-scale three-day online festival at our planned dates in April for over 2000 people, featuring 9 virtual halls of live events, a video screening room, and a “cafeteria” for live chats, all supported by a large crew of volunteer techs. Our 2022 plans for an in-person festival at a hotel site ran afoul of COVID, and in mid-November we pivoted to a second online Festival.

2022

The second online Ralph Page Dance Legacy Weekend drew well over 300 participants. NEFFA Online 2022 featured 11 virtual halls of live events and special online programming like commissioned videos for a massive asynchronous jam and a virtual pub sing, video partnerships with regional organizations like Young Tradition Vermont, and the launch of our NEFFA video archive.

2023

NEFFA is back! With the crest of the COVID pandemic behind us, we were eager to restart our in-person Festival. The last site that we had planned to use, Acton-Boxborough Regional High School, was not available; in fact, no schools in eastern Massachusetts were interested in hosting us, so we had to look elsewhere. We decided to give the Best Western Royal Plaza in Marlborough a try. It was a challenge for the Festival organizers, but we made a great event! We also had a webcast from one performance room for those who could not attend in person.

Festival Locations Through The Years

Boston YWCA

1944 Oct. 28-29

1945 Oct. 27-28

1946 Nov. 16-17

1947 Nov. 15-16

1949 Apr. 23-24

1950 May. 5-6

MIT (Cambridge, MA)

1951 Mar. 30-31

Memorial Auditorium (Worcester, MA)

1952 Apr. 25-26

1953 Apr. 24-25

Tufts University (Medford, MA)

1954 Apr. 9-10

1955 Apr. 1-2

Memorial Auditorium (Worcester, MA)

1956 Apr. 20-21

Phillips Exeter Academy (Exeter, NH)

1957 Apr. 4-5

Tufts University (Medford, MA)

1958 Apr. 11-12

1959 Apr. 24-25

Phillips Exeter Academy (Exeter, NH)

1960 Mar. 25-27

Tufts University (Medford, MA)

1961 Mar. 3-5

Bridgewater (MA) State College

1962 Apr. 13-15

Memorial Auditorium (Lowell, MA)

1963 Apr. 27-29

Manchester (NH) Armory

1964 Apr. 24-25

Saugus (MA) High School

1965 Apr. 23-25

North Kingstown (RI) High School

1966 Apr. 15-17

Natick (MA) High School

1967 Apr. 21-23

1968 Apr. 19-21

1969 May 9-11

1970 Apr. 17-19

King Philip High School (Wrentham, MA)

1971 May 14-16

Wellesley (MA) High School

1972 Apr. 21-23

Brockton (MA) High School

1973 Apr. 20-22

Natick (MA) High School

1974 Apr. 19-21

1975 Apr. 25-27

1976 Apr. 23-25

1977 Apr. 22-24

1978 Apr. 21-23

1979 Apr. 20-22

1980 Apr. 25-27

1981 Apr. 24-26

1982 Apr. 23-25

1983 Apr. 22-24

1984 Apr. 14-15

1985 Apr. 19-21

1986 Apr. 25-27

1987 Apr. 24-26

1988 Apr. 22-24

1989 Apr. 21-23

1990 Apr. 20-22

1991 Apr. 19-21

1992 Apr. 24-26

1993 Apr. 23-25

1994 Apr. 22-24

1995 Apr. 21-23

1996 Apr. 26-28

1997 Apr. 25-27

1998 Apr. 25-27

1999 Apr. 24-26

2000 Apr. 21-23

2001 Apr. 14-16

2002 Apr. 19-21

2003 Apr. 25-27

2004 Apr. 23-25

2005 Apr. 8-10

2006 Apr. 21-23

Mansfield (MA) High & Middle Schools

2007 Apr. 20-22

2008 Apr. 25-27

2009 Apr. 24-26

2010 Apr. 23-25

2011 Apr. 15-17

2012 Apr. 20-22

2013 Apr. 19-21

2014 Apr. 25-27

2015 Apr. 24-26

2016 Apr. 15-17

2017 Apr. 21-23

2018 Apr. 20-22

2019 Apr. 12-14

Virtual Festival

2020 April

2021 April 23-25

2022 April 22-24

Best Western Royal Plaza Hotel & Trade Center (Marlborough, MA)

2023 Apr. 22-24

2024 Apr. 19-21